INSIDE:

NEWS/STORIES/ARTICLES

Book Reviews

Columns/Opinion/Cartoon

Films

International

National

NW/Local

Recipes

Special A.C.E. Stories

Sports

Online Paper (PDF)

CLASSIFIED SECTION

Bids & Public Notices

NW Job Market

NW RESOURCE GUIDE

Consulates

Organizations

Scholarships

Special Sections

Asian Reporter Info

Contact Us

Subscription Info. & Back

Issues

FOLLOW US

Facebook

ASIA LINKS

Currency Exchange

Time Zones

More Asian Links

Copyright © 1990 - 2026

AR Home

Where EAST meets the Northwest

|

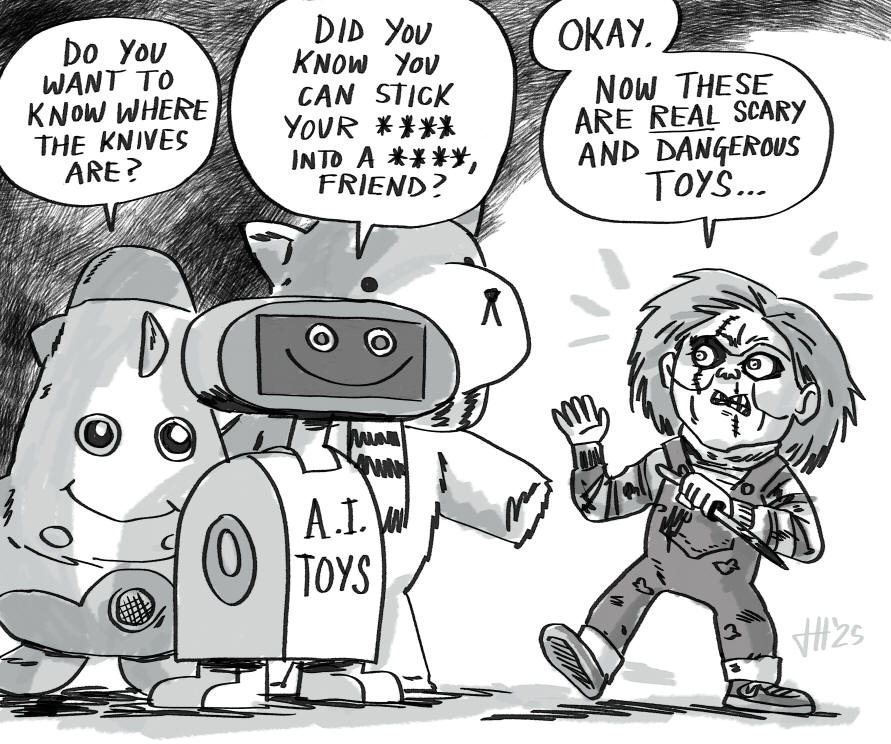

AR cartoon by Jonathan Hill

CUTE BUT CONCERNING. Pictured are artificial intelligence-powered toys tested by consumer advocates at PIRG. Artificial intelligence toys are not safe for kids, according to children’s and consumer advocacy groups urging parents not to buy them during the holiday season. "Kids need lots of real human interaction. Play should support that, not take its place. The biggest thing to consider isn’t only what the toy does; it’s what it replaces. A simple block set or a teddy bear that doesn’t talk back forces a child to invent stories, experiment, and work through problems," said Dr. Dana Suskind, a pediatric surgeon and social scientist who studies early brain development. (Rory Erlich/The Public Interest Network via AP) From The Asian Reporter, V35, #12 (December 1, 2025), page 7. Advocacy groups urge parents to avoid AI toys this holiday season By Barbara Ortutay and Matt O’Brien AP Technology Writers AR Cartoon by Jonathan Hill They’re cute, even cuddly, and promise learning and companionship — but artificial intelligence toys are not safe for kids, according to children’s and consumer advocacy groups urging parents not to buy them during the holiday season. These toys, marketed to kids as young as 2 years old, are generally powered by AI models that have already been shown to harm children and teenagers, such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT, according to an advisory published by the children’s advocacy group Fairplay and signed by more than 150 organizations and individual experts such as child psychiatrists and educators. "The serious harms that AI chatbots have inflicted on children are well-documented, including fostering obsessive use, having explicit sexual conversations, and encouraging unsafe behaviors, violence against others, and self-harm," Fairplay said. AI toys, made by companies including Curio Interactive and Keyi Technologies, are often marketed as educational, but Fairplay says they can displace important creative and learning activities. They promise friendship but disrupt children’s relationships and resilience, the group said. "What’s different about young children is that their brains are being wired for the first time and developmentally it is natural for them to be trustful, for them to seek relationships with kind and friendly characters," said Rachel Franz, director of Fairplay’s Young Children Thrive Offline Program. Because of this, she added, the trust young children are placing in these toys can exacerbate the types of harms older children are already experiencing with AI chatbots. A separate report by Common Sense Media and psychiatrists at Stanford University’s medical school warned teenagers against using popular AI chatbots as therapists. Fairplay, a 25-year-old organization formerly known as the Campaign for a Commercial-Free Childhood, has been warning about AI toys for years. They just weren’t as advanced as they are today. A decade ago, during an emerging fad of internet-connected toys and AI speech recognition, the group helped lead a backlash against Mattel’s talking Hello Barbie doll that it said was recording and analyzing children’s conversations. This time, though AI toys are mostly sold online and more popular in Asia than elsewhere, Franz said some have started to appear on store shelves in the U.S. and more could be on the way. "Everything has been released with no regulation and no research, so it gives us extra pause when all of a sudden we see more and more manufacturers, including Mattel, who recently partnered with OpenAI, potentially putting out these products," Franz said. It’s the second big seasonal warning against AI toys since consumer advocates at U.S. PIRG called out the trend in its annual "Trouble in Toyland" report that typically looks at a range of product hazards, such as high-powered magnets and button-sized batteries that young children can swallow. This year, the organization tested four toys that use AI chatbots. "We found some of these toys will talk in-depth about sexually explicit topics, will offer advice on where a child can find matches or knives, act dismayed when you say you have to leave, and have limited or no parental controls," the report said. One of the toys, a teddy bear made by Singapore-based FoloToy, was later withdrawn, its CEO told CNN. Dr. Dana Suskind, a pediatric surgeon and social scientist who studies early brain development, said young children don’t have the conceptual tools to understand what an AI companion is. While kids have always bonded with toys through imaginative play, when they do this they use their imagination to create both sides of a pretend conversation, "practicing creativity, language, and problem- solving," she said. "An AI toy collapses that work. It answers instantly, smoothly, and often better than a human would. We don’t yet know the developmental consequences of outsourcing that imaginative labor to an artificial agent — but it’s very plausible that it undercuts the kind of creativity and executive function that traditional pretend play builds," Suskind said. Beijing-based Keyi, maker of an AI "petbot" called Loona, didn’t return requests for comment, but other AI toymakers sought to highlight their child safety protections. California-based Curio Interactive makes stuffed toys, like Gabbo and rocket-shaped Grok, that have been promoted by the pop singer Grimes. The company said it has "meticulously designed" guardrails to protect children and the company encourages parents to "monitor conversations, track insights, and choose the controls that work best for their family." In response to the earlier PIRG findings, Curio said it is "actively working with our team to address any concerns, while continuously overseeing content and interactions to ensure a safe and enjoyable experience for children." Another company, Miko, based in Mumbai, India, said it uses its own conversational AI model rather than relying on general large language model systems such as ChatGPT in order to make its product — an interactive AI robot — safe for children. "We are always expanding our internal testing, strengthening our filters, and introducing new capabilities that detect and block sensitive or unexpected topics," said CEO Sneh Vaswani. "These new features complement our existing controls that allow parents and caregivers to identify specific topics they’d like to restrict from conversation. We will continue to invest in setting the highest standards for safe, secure, and responsible AI integration for Miko products." Miko’s products are sold by major retailers such as Walmart and Costco and have been promoted by the families of social media "kidfluencers" whose YouTube videos have millions of views. On its website, it markets its robots as "Artificial Intelligence. Genuine friendship." Ritvik Sharma, the company’s senior vice president of growth, said Miko actually "encourages kids to interact more with their friends, to interact more with the peers, with the family members, etc. It’s not made for them to feel attached to the device only." Still, Suskind and children’s advocates say analog toys are a better bet for the holidays. "Kids need lots of real human interaction. Play should support that, not take its place. The biggest thing to consider isn’t only what the toy does; it’s what it replaces. A simple block set or a teddy bear that doesn’t talk back forces a child to invent stories, experiment, and work through problems. AI toys often do that thinking for them," she said. "Here’s the brutal irony: when parents ask me how to prepare their child for an AI world, unlimited AI access is actually the worst preparation possible." Read the current issue of The Asian Reporter in

its entirety!

|